A Strategic Analysis of Post-Sale Discounts Under GST

Executive Summary

The Central Board of Indirect Taxes and Customs (CBIC), through Circular No.

251/08/2025-GST dated September 12, 2025, has introduced a landmark clarification on

the Goods and Services Tax (GST) treatment of secondary and post-sale discounts. This

directive represents a significant maturation in GST policy, moving away from previously

contentious and administratively burdensome positions towards a more pragmatic and

legally sound framework. The circular provides definitive guidance on three core areas of

dispute: the non-reversal of Input Tax Credit (ITC) on discounts settled via financial or

commercial credit notes; a nuanced test for treating discounts as consideration for a

dealer’s onward supply; and a “bright line” distinction between non-taxable trade

incentives and taxable promotional services.

While the circular brings welcome clarity and is poised to reduce litigation, its subtext

reveals a critical shift in the compliance landscape. The burden of proof now rests

squarely on the taxpayer, necessitating robust documentation and contractual precision.

This report uncovers these hidden implications, highlighting how the circular transforms

the issuance of credit notes into a strategic commercial decision and elevates the

importance of meticulously drafted agreements. The analysis concludes that Circular No.

251, while resolving long-standing ambiguities, demands a proactive strategic

realignment of commercial contracts, accounting practices, and internal financial

controls for businesses to navigate the new compliance paradigm effectively.

Anatomy of Circular No. 251/08/2025-GST

The circular meticulously dissects three primary areas of ambiguity that have historically

plagued taxpayers and tax authorities alike. It provides clear, scenario-based

clarifications that are anchored in the legal provisions of the CGST Act, 2017.

The ITC Conundrum Solved: Non-Reversal on Financial/Commercial Credit Notes

The most significant clarification provided by Circular No. 251 is the definitive stance on

Input Tax Credit (ITC) in the hands of the recipient of a post-sale discount. The circular

states unequivocally that a recipient, such as a dealer or distributor, is not required to

reverse the ITC availed on an original supply when a post-sale discount is settled through

a financial or commercial credit note.

The legal foundation for this position rests on the distinction between two types of credit

notes. A tax credit note, issued under Section 34 of the CGST Act, 2017, is a statutory

document that formally reduces the value of the original supply and, consequently, the

supplier’s output tax liability. This reduction in tax liability at the supplier’s end

necessitates a corresponding reversal of ITC at the recipient’s end to maintain the

integrity of the value-added tax chain.

In contrast, a financial or commercial credit note is a purely commercial document used

to adjust the payment value between parties for reasons like volume rebates or special

incentives, without altering the tax component of the original transaction. As this type of

credit note does not reduce the supplier’s original output tax liability, the government’s

revenue from the transaction remains unchanged. Therefore, the circular concludes that

there is no legal basis to compel the recipient to reverse the ITC they have claimed. This

position builds upon the foundation laid in the earlier Circular No. 92/11/2019-GST and

provides a clear safe harbor, resolving a major compliance risk that had been

persistent source of disputes.

This clarification introduces a distinct strategic choice for businesses when settling

discounts. A supplier can issue a tax credit note under Section 34, which reduces their

own GST outflow but imposes a compliance burden on the recipient to reverse ITC.

Alternatively, the supplier can issue a financial/commercial credit note, forgoing the

immediate tax benefit but allowing the recipient to retain their full ITC. This transforms

the credit note mechanism from a simple accounting entry into a tactical commercial

decision, enabling a supplier to balance their own tax cost against the benefits of

maintaining a strong commercial relationship with a key dealer who may be unwilling to

undertake the complexities of ITC reversal.

Redefining 'Consideration' in Multi-Tier Supply Chains

The circular introduces a crucial two-pronged test to determine whether a discount

provided by a manufacturer to a dealer should be treated as part of the consideration

for the dealer’s subsequent sale to an end customer.

Scenario 1: No Addition to Value of Supply

In a standard supply chain where a manufacturer sells to a dealer on a principal-toprincipal basis, and there is no pre-existing agreement between the manufacturer and

the end customer, the transaction is viewed as two independent sales. Any post-sale

discount offered by the manufacturer to the dealer is treated merely as a reduction in

the dealer’s purchase price. It is not considered an “inducement” or third-party

consideration for the dealer’s onward supply to the customer. The discount’s purpose is

to improve the dealer’s competitiveness or reward sales performance, and it does not

affect the value of the second transaction between the dealer and the end customer.

Scenario 2: Addition to Value of Supply

The treatment changes fundamentally if the manufacturer has a prior agreement with an

end customer to provide goods at a specific reduced price. To facilitate this, the

manufacturer may issue a credit note to the dealer, effectively compensating the dealer

for the price reduction offered to the end customer. In this specific scenario, the circular

clarifies that the discount amount reimbursed by the manufacturer to the dealer

constitutes consideration. This is based on the definition of “consideration” under

Section 2(31) of the CGST Act, which includes payments made by any person other than

the recipient of the supply.

ot Pockettax

Therefore, this amount must be added to the price paid by the end customer to arrive at

the dealer’s total taxable value of supply. This was a contentious issue, with advance

rulings like the one in the Castrol case creating significant uncertainty.

This clarification establishes a direct causal link between the existence of

manufacturer-end customer agreement and the tax treatment at the dealer level. The

presence of such a contract fundamentally alters the nature of the discount from

simple price adjustment to a third-party consideration. This creates a new compliance

risk for dealers, as their tax liability is now directly influenced by the contractual

arrangements of the manufacturer, a party with whom they might not have full visibility.

It underscores the need for greater transparency and communication across the supply

chain to ensure correct valuation.

The Bright Line Test: Differentiating Trade Incentives from Taxable Services

Circular No. 251 establishes a clear “bright line test”to distinguish between a non-taxable

trade discount and a taxable consideration for a promotional service. A post-sale

discount will not be treated as consideration for a service provided by the dealer unless

there is an explicit agreement for the dealer to perform specific and distinct

promotional activities for a defined consideration.

The circular introduces the “dealer’s own benefit” principle, recognizing that dealers

often undertake routine promotional activities-such as ensuring prominent shelf

placement, running small marketing drives, or pushing sales-primarily for their own

commercial benefit to increase their own revenue. In such cases, the discount from the

manufacturer is merely a price reduction tool to enhance the dealer’s competitiveness

and is not a payment for any service rendered to the manufacturer.

GST becomes leviable only when the relationship shifts from a simple buyer-seller

dynamic to one involving a service contract. This occurs when a dealer is contractually

obligated to perform specific services on behalf of the manufacturer, such as cobranding initiatives, dedicated advertising campaigns, arranging exhibitions, or providing

specialized customer support, and is compensated for these activities. This creates

clear demarcation between a price adjustment and a B2B service transaction, which

would require the dealer to issue a tax invoice to the manufacturer for the service

provided.

While the “explicit agreement” criterion provides a clear line of defense for taxpayers, it

is a double-edged sword. It shields businesses from arbitrary recharacterization of

discounts by tax authorities where no service contract exists. However, it simultaneously

creates a new focal point for tax audits. Auditors will now intensify their scrutiny of all

agreements, correspondence, and internal communications related to discount schemes.

Any language that even implicitly suggests a service obligation-such as “in return for

enhanced visibility” or “to support our marketing efforts”-could be used to argue that a

de facto agreement for services exists, thereby challenging the non-taxable nature of the

discount. This effectively shifts the battleground from interpreting the nature of the

discount to scrutinizing the language of the commercial arrangement.

Uncovering the Hidden Points: Reading Between the Lines

Beyond its explicit clarifications, Circular No. 251 carries deeper, implicit consequences that

will reshape compliance strategies and the landscape of tax litigation.

The Onus of Documentation: The New Compliance Frontier

The circular’s repeated emphasis on conditions like “explicit agreement” and the “principalto-principal” nature of transactions implicitly places a heavy burden of proof on the taxpayer.

It is no longer sufficient to simply issue a credit note; businesses must be prepared to defend

the commercial substance and intent behind every discount. This necessitates a proactive

and meticulous approach to documentation, including:

Supplier-Dealer Agreements: These must be drafted with precision, clearly defining the

relationship and the nature of all potential discounts.

Contracts for Marketing Services: Any arrangements for promotional activities must be

formalized in separate, distinct contracts with a clear scope of work and specified

consideration.

Credit Note Documentation: Credit notes should unambiguously state their nature

(e.g., “Financial/Commercial Credit Note not affecting original GST liability”).

Internal Policies: Businesses should develop clear internal policies that guide sales and

finance teams on the classification and documentation of different discount schemes.

The clarity offered by the circular is therefore conditional upon a taxpayer’s ability to

substantiate their position with robust documentation. A reactive approach is no longer

viable. Businesses must structure their commercial arrangements with the assumption that

they will be scrutinized during an audit. The absence of a clear, well-drafted agreement will

likely be interpreted by tax authorities in their favor, making proactive defense a nonnegotiable aspect of compliance.

Navigating the "Principal-to-Principal" Safe Harbor

The circular frequently cites the “principal-to-principal” relationship between a manufacturer

and a dealer as a cornerstone for its clarifications. In such a relationship, the dealer acquires

legal title to the goods and assumes the associated risks, distinguishing it from a principal agent relationship where an agent acts on behalf of the principal and different valuation

rules apply.

While this provides a safe harbor, it also presents a hidden risk of recharacterization. Tax

authorities may look beyond the mere labeling of the relationship in the contract to

examine its substance. If a manufacturer exerts excessive control over a dealer’s

operations-for example, by dictating the final selling price to all customers, controlling

inventory levels, or bearing a significant portion of the risk of loss-it could be argued that

the relationship is, in substance, one of a principal and an agent. A successful

recharacterization would invalidate the tax treatment prescribed in Circular 251 for

principal-to-principal transactions and could trigger the application of different valuation

norms, leading to significant and unforeseen tax liabilities. Businesses must ensure that

their operational conduct and agreements consistently reflect a true principal-to-principal

dynamic.

Defining the Undefined: Future Litigation Hotspots

While Circular 251 resolves many past disputes, it inadvertently sows the seeds for future

litigation by using key terms without providing statutory definitions. Terms such as “explicit

agreement,” “distinct promotional activities,” and “routine trade discounts” remain open to

interpretation. This ambiguity creates potential new areas of conflict:

What constitutes an “explicit” agreement? Must it be a formal, notarized contract, or

can a series of emails suffice?

What is the threshold that separates a dealer’s “routine” marketing effort from a

“distinct” service performed for the manufacturer?

Can a performance-based incentive for achieving a sales target be considered a

“routine trade discount,” or is it consideration for the “distinct service” of achieving that

target?

The next wave of litigation will likely pivot from debating the fundamental taxability of

discounts to arguing the factual matrix surrounding these undefined terms. The outcome

of such disputes will depend heavily on the specific facts of each case and, crucially, the

quality and clarity of the taxpayer’s documentation.

The Unspoken Impact on the Advance Ruling Landscape

The issue of post-sale discounts has been a subject of numerous, often contradictory,

rulings from various state-level Authorities for Advance Rulings (AARs). Rulings such as

those in the cases of MRF Limited and Castrol created significant confusion and

inconsistency across the country.

Although a circular is not legally binding on judicial or quasi-judicial bodies like AARs, it

is binding on field formations of the tax department. Circular 251 acts as a powerful

tool of policy harmonization by executive fiat. By establishing a clear and uniform

national standard, it will heavily influence the reasoning in future advance rulings and

provide taxpayers with a strong basis to challenge assessments that rely on older,

contradictory precedents. It signals the CBIC’s clear intent to end the state-level

fragmentation of tax policy on this critical issue. While an AAR could theoretically rule

contrary to the circular, it would create a paradoxical situation where the assessing

officer would be bound by the circular’s guidance, making such a ruling difficult to

implement and legally tenuous.

The Policy Evolution: From Confusion to Clarity

Circular No. 251 is not a standalone directive but the culmination of a multi-year policу

evolution marked by course corrections and a gradual shift towards pragmatism.

Understanding this journey is crucial to appreciating the circular’s significance.

The initial attempt at clarification came with Circular No. 92/11/2019-GST, which

addressed various sales promotion schemes. It correctly stated that

financial/commercial credit notes do not impact the supplier’s tax liability but left the

recipient’s ITC eligibility ambiguous, an omission that led to adverse advance rulings

and widespread confusion.

This was followed by the highly controversial Circular No. 105/24/2019-GST. This

circular introduced a legal fiction by suggesting that certain discounts given to dealers

could be treated as consideration for a deemed promotional service provided by the

dealer back to the supplier. This position was widely criticized by tax experts as an

overreach of executive power, legally unsound, and contrary to established commercial

realities, leading to significant industry pushback.

More recently, Circular No. 212/6/2024-GST was issued as an interim procedural

measure to operationalize the conditions of Section 15(3)(b) of the CGST Act. It

introduced the administratively burdensome requirement for suppliers to obtain

certificates from Chartered Accountants (CAs) or Cost Accountants (CMAS) to prove that

recipients had reversed their ITC, creating significant compliance friction and practical

difficulties for businesses.

Circular No. 251 represents a decisive course correction. It systematically dismantles

the problematic aspects of its predecessors. It directly resolves the ITC ambiguity of

Circular 92, unequivocally rejects the deemed service fiction of Circular 105, and

renders the procedural hurdles of Circular 212 redundant for discounts settled via

commercial credit notes. This trajectory reveals a significant shift in the CBIC’s policymaking philosophy-from an initially aggressive, revenue-centric approach to a more

pragmatic stance that prioritizes tax certainty and alignment with business practices.

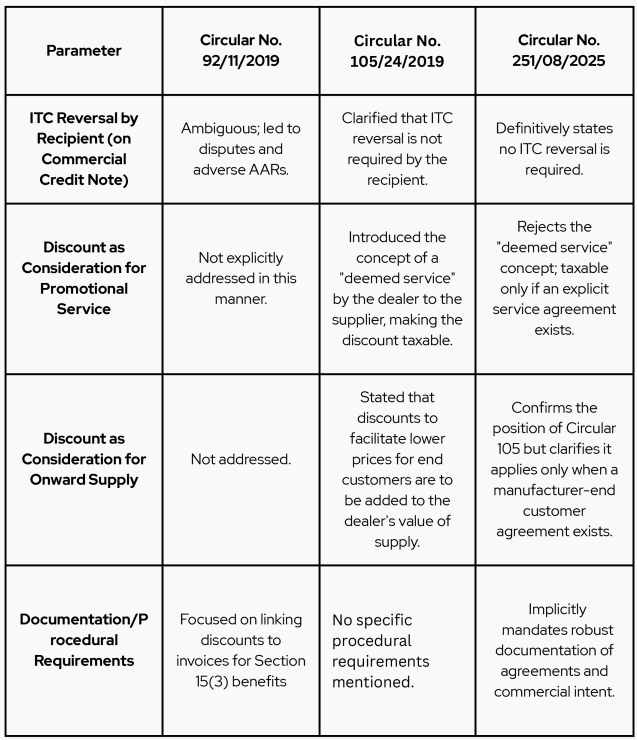

The following table provides a comparative analysis of the CBIC’s evolving stance:

An Operational Blueprint for GST Compliance

The clarifications in Circular 251 necessitate a proactive review and potential overhaul

of existing business practices. The following blueprint provides actionable guidance for

ensuring compliance.

Contractual Redrafting and Best Practices

Businesses must immediately review and redraft their agreements with dealers,

distributors, and other supply chain partners to align with the circular’s principles. Key

clauses to incorporate include:

- A clear and unambiguous statement establishing the commercial relationship as

“principal-to-principal.” - Explicit definitions for all potential discounts (e.g., “volume rebate,” “prompt

payment discount,” “special trade discount”) with a clear declaration that they are

price adjustments and not consideration for any service. - A “severability” clause for promotional services. If any such services are

contemplated, they must be covered in a separate, distinct agreement that specifies

the scope of work, deliverables, and the consideration payable. - Clauses that address the handling of manufacturer-funded discounts for end

customers, ensuring the dealer is contractually informed of any underlying

agreements and their obligation to adjust the taxable value accordingly.

Accounting and Credit Note Management

The circular solidifies the strategic divide between two types of credit notes, requiring a

conscious decision-making process:

- Tax Credit Note (under Section 34): This reduces the supplier’s output tax liability

but requires the recipient to reverse their ITC. It must be linked to the original tax

invoice(s). Recent amendments have provided flexibility, allowing a single credit

note to be linked to multiple invoices, easing a long-standing compliance burden,

particularly for the FMCG sector. - Financial/Commercial Credit Note: This does not affect the original GST liability

for the supplier and, consequently, the recipient is not required to reverse ITC. It

offers greater commercial flexibility as it does not need to be linked to specific

invoices.

Businesses should develop a decision matrix to guide the choice of credit note,

considering factors such as the GST value of the discount, the compliance sophistication

of the recipient, the commercial importance of the relationship, and the supplier’s own

tax position.

Internal Controls and Audit Preparedness

Given the increased focus on documentation, robust internal controls are essential. This

includes:

- Developing a Formal Discount Policy: Create a comprehensive “Discount Policy

Manual” that is communicated across sales, marketing, and finance departments.

This manual should classify different types of discounts, outline the approval process,

and specify the documentation required for each. - Preparing for Audit Scrutiny: Tax audits will now focus on the substance and

documentation of discount arrangements. A checklist for audit preparedness should

include: - Maintaining a centralized repository of all supplier-dealer agreements and service

contracts. - Ensuring all credit notes are clearly labeled as either “Tax Credit Note” or

“Financial/Commercial Credit Note.” - Archiving all relevant correspondence (emails, letters) that supports the commercial

rationale for discounts, ensuring the language used does not inadvertently imply a

service obligation.

Sectoral Deep Dive: Impact and Case Studies

The principles of Circular 251 will have a varied but significant impact across different

industries, depending on their specific commercial practices.

Fast-Moving Consumer Goods (FMCG)

The FMCG sector is characterized by complex, multi-layered discount schemes designed

to drive volume through extensive distribution networks. A key industry challenge is

maintaining sacrosanct low price points (e.g., Rs. 5, Rs. 10), where benefits of cost

reductions are often passed on through increased grammage rather than price cuts.

The circular provides immense relief and strategic flexibility. Volume and target-based

discounts can now be confidently settled via commercial credit notes without triggering

ITC reversal for distributors, drastically simplifying compliance. The logic of the circular

also reinforces the position on promotional schemes like ‘Buy One Get One,’ treating

them as a single composite supply with full ITC eligibility, as clarified in Circular 92.

However, payments made to retailers for specific services like prime shelf space or instore displays will now clearly fall under the “taxable service” category, requiring a

separate agreement and a tax invoice from the retailer. This clarity allows FMCG

companies to design more aggressive and flexible trade schemes without the looming

fear of tax litigation.

Automotive Industry

The automotive sector operates on high-value transactions and a system of targetbased incentives, performance bonuses, and rebates paid by Original Equipment

Manufacturers (OEMs) to dealers. The taxability of these incentives has been a major

point of contention, as highlighted by the pre-GST CESTAT ruling in the Vipul Motors

case, which held such incentives to be non-taxable.

Circular 251 provides the clear framework under GST that was previously missing. An

incentive purely linked to achieving a sales volume target can be treated as a nontaxable trade discount settled via a commercial credit note. However, if an incentive is

linked to specific dealer actions, such as organizing test drive events or running a соbranded advertising campaign, it is unequivocally a consideration for a taxable service,

for which the dealer must issue a tax invoice to the OEM. Furthermore, fleet rebates

provided to dealers to facilitate sales to large corporate customers fall squarely under

the scenario where the discount must be added to the dealer’s transaction value. The

circular thus resolves the ambiguity that persisted in the GST era by establishing

clear, contract-based test.

Pharmaceutical Sector

The pharmaceutical industry’s promotional model is unique, centered on the distribution of “physician samples” free of cost to medical practitioners. This practice has been in direct conflict with Section 17(5)(h) of the CGST Act, which blocks ITC on goods disposed of as “free samples”. The industry has long argued that these are not consumer freebies but essential and regulated marketing tools integral to their business.

While Circular 251 does not directly address Section 17(5)(h), its underlying principles offer a new line of argument. The traditional tax view holds that the sample is a “gift” or “free sample,” mandating ITC reversal. However, leveraging the logic of the circular, a pharma company can now more strongly argue that distributing physician samples is part of its own business promotion, not a service rendered to the doctor. Since there is no “explicit agreement” for the doctor to provide a promotional service in return for the samples, the transaction should not be characterized as a supply of service. This does not automatically unblock the credit under the specific restriction of Section 17(5) (h), but it significantly strengthens the industry’s case that these are legitimate business promotion expenses, not gifts. This conceptual reframing could be pivotal in future representations to the GST Council for a specific carve-out for the pharma sector, a possibility that has been reported.

Conclusion and Forward Outlook

Circular No. 251/08/2025-GST is a landmark piece of subordinate legislation that brings long-awaited certainty and pragmatism to the GST treatment of post-sale discounts. It successfully balances the interests of revenue with the commercial realities of modern trade, resolving years of ambiguity and reducing the scope for litigation.

The key strategic imperatives for businesses are now clear: a critical need to overhaul commercial agreements to reflect the circular’s distinctions, a conscious and strategic approach to the use of different credit note mechanisms, and the maintenance of an impeccable, audit-ready trail of documentation to substantiate the nature of every discount.

Looking forward, while the circular clarifies the treatment of discounts, other complex areas in GST valuation remain. Issues surrounding related-party transactions, the valuation of composite and mixed supplies in specific contexts, and the treatment of non-monetary consideration continue to pose challenges. The clear and pragmatic approach demonstrated in Circular 251 provides a hopeful precedent that these remaining ambiguities may also be addressed through future policy interventions from the CBIC and the GST Council, paving the way for a more streamlined and certain GST regime.